Welcome to another edition of Miss Me with That Bullshit, a series of opinion pieces where the topics—and the content—might not be to your liking.

After the interest generated by the first article in this series, which heavily featured my personal disdain for Resident Evil 4 and why that overhyped piece of shit doesn’t deserve a remake over something that truly needs it—like Resident Evil: Code Veronica or other CAPCOM franchises—I thought I’d continue riding my lovely, hate-fueled train of unpopular opinions and talk about something else close to my heart. Something that’s been crushed by people who blindly praise what they think is “new and different,” but ultimately destroyed a beloved franchise: Star Wars.

At the time of publishing, it’s May 4th, 2020. The date has become noteworthy thanks to the pun on the classic phrase “May the Force be with you,” turning it into “May the 4th be with you” or “May the Fourth be with you.” On this day, fans celebrate the long-running franchise known as Star Wars. As I write this, I’ve started my 3-day Star Wars tradition: watching all the main series Star Wars movies in order (not counting things like Rogue One, Solo, the Holiday Special, the Ewok movies, etc.) at a rate of three movies per day. So with today being May 4th, I begin with Episodes I, II & III. Tomorrow brings the main event with IV, V & VI. And finally, I’ll begrudgingly slog through the Disney trilogy—Episodes VII, VIII & IX.

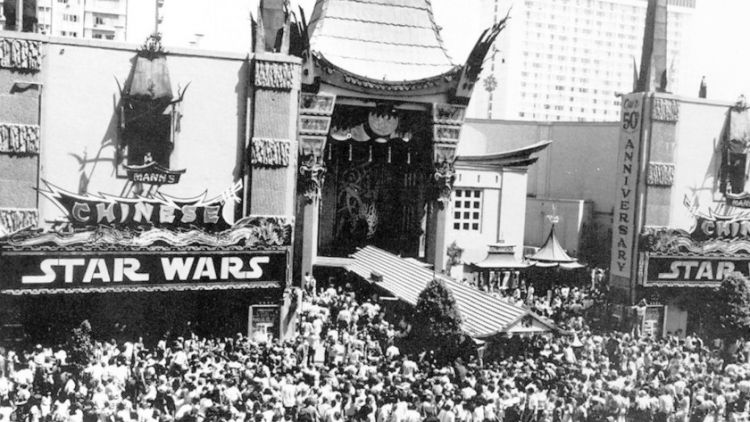

Star Wars means a lot to many people around the world. It’s something passed down from one generation to the next—first by our parents, and now by us. It was a pop culture phenomenon before the phrase “pop culture” even existed. It predates the “normal people vs. nerds” school hallway battles. It’s something so magical and impactful that it deserves to be celebrated with respect and given the reverence reserved for the greatest masterpieces of creation… But it’s not.

Thanks to the internet and its ability to create division within any fanbase—and the rise of “nerd culture” being embraced by people who once scorned it with the hatred of a thousand suns—the Star Wars fandom is more fractured than ever. What was once a united galaxy of fans praising the franchise as a whole has become a war-torn realm. On one side are those who support what Disney has done to Star Wars since purchasing it for billions back in 2012 (i.e., the introduction of Rey, Kylo, and the complete rewriting of everything that came before Episode VII: The Force Awakens). On the other side are those of the “old guard,” clinging to an “outdated” series of films that meant nothing—at least until Disney supposedly “fixed” them (i.e., fans of the original trilogy, and some who also appreciate the prequels). This latter group is often labeled as basement-dwelling neckbeards who live with their parents and are all over the age of 30.

I’m going to tell you right away—and as you might have guessed from my writing already—I’m firmly in the camp of those who prefer the original trilogy (and I don’t mind some of the prequels, too). I love Episodes IV, V, and VI, as those were the ones I grew up with. I watched them on TV and VHS back in the day. I even got to see the Special Edition remasters in the cinema—my mother made me go, wanting me to have the same experience she had as a kid seeing the originals on the big screen. I saw the prequels in the cinema and again on DVD. Later, I got to share the experience of watching Star Wars with my little brother during the May 4th/5th marathon screenings, which included the series up to that point and the Disney trilogy (which he didn’t like either).

For me, Star Wars holds a special place in my heart because it’s a shared experience—something that created a lasting connection with my family. My mother, my little brother, and I now share a bond through this franchise that nothing else on this planet could replicate.

However, things changed for me as a Star Wars fan. With the release of Episode VII: The Force Awakens, I was thrown into a story that felt nothing like what I knew—yet somehow tried to be familiar at the same time. When the movie opened with the classic Star Wars text crawl, I was a kid again. But once Rey appeared on screen, I knew I wasn’t in for the same kind of ride I’d taken so many years ago.

When Disney officially bought the Star Wars brand, people were understandably worried about what would happen to the beloved franchise. One of the worst fears at the time was that Disney would somehow inject their own characters into the universe through a mix of animation and live-action (as seen in the video above). Honestly, looking back on that now… I’d almost prefer it over what we actually got.

With George Lucas (somewhat thankfully) stepping away from the series, the reins were handed to J.J. Abrams—the man who, at the time, had successfully revitalized the Star Trek movie series with a reboot that paid homage to the originals while still offering something new. That approach managed to get both old and new fans to at least agree to disagree on most of the contentious points. With Abrams at the helm, Star Wars looked to be in good hands.

But Disney had to make sure they were firmly in control. Enter Kathleen Kennedy.

For those unfamiliar with the name, you’ll be hearing it a lot—probably to the point of exhaustion. Kennedy began her career as an assistant to the legendary Steven Spielberg, working on classics like E.T., Jurassic Park, and the Indiana Jones films. She was instrumental in the creation of Amblin Entertainment and quickly rose to become one of Hollywood’s top producers. Eventually, she launched her own production company with her husband… which didn’t last long. Not long after, she joined Lucasfilm as co-chair—just before Disney acquired the company.

When George Lucas stepped down as part of that deal, Kathleen Kennedy became President of Lucasfilm, and now holds a firm seat in Disney’s war room when it comes to all things Star Wars.

This is where things start to get murky. From the outset, rumours began circulating online that Kathleen Kennedy had orchestrated the Lucasfilm sale—allegedly including a side deal that would ensure her continued place on the Lucasfilm board and grant her significant influence within Disney. These rumours claim she was ultimately placed in full control of the Star Wars brand once George Lucas stepped aside. Some even suggest it was her idea to convince Lucas to sell and retire, pushing him to sign everything over to Disney.

None of this can be confirmed, of course, as those involved during that time—including Lucas himself—have not spoken out publicly against Disney or Kennedy. However, what followed has been confirmed by Disney and Lucasfilm insiders, as well as cast members and production workers. (One of the best sources for these revelations is the YouTube channel Clownfish TV, which reportedly received a substantial amount of insider information during the production of the Disney trilogy.)

It’s also worth noting that as part of the Disney deal, all previously established Star Wars Expanded Universe content—TV shows, comics, fan films, novels, and more, both official and unofficial—was deemed non-canonical. This move allowed Disney to continue the universe on its own terms, free from the obligations or continuity of decades of storytelling created by non-Disney personnel.

Originally, The Force Awakens was supposed to be based on a partially completed script by George Lucas. That script included the original trilogy characters—Luke, Leia, Han, and others—set years later, with the idea being that their children would transition into the lead roles. Han would reunite with his family, Luke would rebuild the Jedi Order, and Leia would lead the Galactic Senate. The plan was for the new trilogy to evolve naturally over time, easing the shift in focus and avoiding any jarring changes for longtime fans.

But that wasn’t what Disney or Kennedy wanted. Disney was more interested in creating an entirely new storyline with fresh characters it could own outright and market easily. The older characters would be relegated to supporting roles, showing up only in side stories or cameos between the main entries.

This approach suited Kennedy, who is widely known to be a hardcore third-wave feminist. She reportedly saw this as an opportunity to push a new vision for Star Wars—a vision captured in her infamous phrase, “The Force is Female.” From the outset, the plan was to have a female lead front and centre throughout the trilogy—one who would surpass every previous character in power, importance, and capability.

Enter Rey—a blank slate for Kennedy to project her ideals and agenda onto a new generation of Star Wars fans. Kennedy didn’t seem fond of the existing fan base, which she reportedly viewed as predominantly “white male nerds” (despite the fact that Star Wars has always had a diverse global fan base across all races, genders, and backgrounds). She envisioned a new wave of Star Wars fans—specifically female—who would feel empowered and dominant in a world where, in her view, men were largely sexist, misogynistic, and dismissive of all things female.

Kennedy wanted Rey to be everywhere—a new Luke Skywalker for people like her, only better. To ensure that Rey would be embraced as the ultimate hero, Kennedy made sure Rey could do everything Jedi before her had spent years training to master—effortlessly, without guidance, struggle, or formal instruction.

Everyone was supposed to be in awe of Rey—praising her innate, natural talents and hailing her as the new face of Star Wars. But Kennedy knew she wouldn’t win over the younger, more impressionable online crowd—then dominated by Tumblr—unless she also gave them a character they could obsess over and emotionally project onto. Thus, Kylo Ren was born.

Kylo Ren exists almost entirely as a “shipping” device—created to appeal to the new generation of Star Wars fans eager to imagine forbidden romances and emotional redemption arcs. He’s a well-muscled, emotionally distant, tortured, attractive male antagonist who could be “saved” by the love of the heroine. He was never meant to be a truly menacing villain; rather, he was designed to be the misunderstood “bad boy” that Rey—and fans—could fantasize about reforming.

From the moment Kylo first appeared on screen, the reaction wasn’t fear or disdain. Instead, the internet swooned. Almost immediately, fanfiction and art portraying a romantic relationship between Rey and Kylo—dubbed “Reylo”—exploded online. The narrative formed quickly: Rey, the all-powerful heroine who doesn’t need a man, still longs to redeem the brooding, misguided Kylo. It was perfect fuel for fan-created content and was consumed in droves.

And here’s the contradiction: Rey is supposed to represent the modern, independent woman—the “I don’t need no man” archetype. Yet at the same time, her character arc involves pining after the emotionally unavailable bad boy, convinced she can change him with her love. It’s a strange, conflicting message—one that tries to have it both ways but ends up weakening both sides of her character.

With the new female fan base firmly in place, it was time to begin Phase 2: assigning blame. You see, J.J. Abrams had done a decent job of meeting Kennedy’s demands while still delivering a story that resonated with older fans. He included meaningful cameos from legacy characters, crafted a plot that bridged the old and new generations, and ended The Force Awakens on a note that left audiences eager for more.

But that wasn’t enough for Kennedy. Her vision for Star Wars was one dominated by female leads and modern progressive ideals—not the space western action series that fans had come to love. She wasn’t interested in building on the past. She wanted it erased—along with the “white male nerds” who had long been the stewards of the original trilogy.

So, Kennedy embraced a trend that has sadly persisted to this day, one encouraged by a media too afraid to challenge its most vocal idealists: blame. Everything wrong with modern pop culture, they claimed, was the fault of “white male nerds who never grew up.” These fans were now cast as villains—accused of rejecting progress, feminism, and inclusivity in favour of nostalgia and gatekeeping.

Mainstream media outlets quickly latched onto this narrative. Suddenly, the older Star Wars fan base—the ones who had kept the franchise alive through decades of ups and downs—were no longer welcome. Star Wars didn’t belong to them anymore. It now belonged to a new generation that embraced progressive ideals and feminist reinvention.

Many older fans, myself included, stood firm in our opinions. We saw The Force Awakens as a respectable callback to the original trilogy—honouring what came before—but we also noticed something off. The new characters felt forced, their dialogue unnatural, their roles seemingly lifted straight out of Tumblr fanfiction. And we feared that if left unchecked, this direction could spell the end of Star Wars as both a marketable brand and an enjoyable story.

Then came the news that confirmed our worst suspicions—even if no one wanted to believe it, thanks to the combined might of Kennedy, Disney, and the media:

J.J. Abrams would not be returning to direct Episode VIII…

Due to a deal with Paramount Pictures and Netflix, J.J. Abrams had to bow out of directing Episode VIII in order to produce Star Trek Beyond and The Cloverfield Paradox, respectively. This left Kathleen Kennedy free to choose a new writer and director for Episode VIII—someone who would follow her vision without resistance. Enter Rian Johnson, a relatively unknown director at the time, whose most notable work was the sci-fi film Looper. Johnson had a reputation for subverting expectations and avoiding traditional storytelling norms, which made him the perfect candidate in Kennedy’s eyes. She saw someone she could easily control, someone who would help her reshape Star Wars into what she wanted it to be.

Kennedy gave Johnson a single directive: burn it all down.

She wanted Star Wars scorched—its legacy dismantled, its past forgotten. And Johnson, incentivized by the promise of directing not only Episode IX but also his own new trilogy if The Last Jedi succeeded, was more than willing to oblige.

And so we got The Last Jedi—a film that did exactly what Kennedy wanted. It burned nearly everything that came before it, including the groundwork laid by The Force Awakens. We were introduced to new characters like Rose Tico, a mechanic positioned to become the “new Han Solo” in Kennedy’s eyes—not because of personality or narrative weight, but because she was female and Asian, ticking the diversity boxes. She was also paired with Finn to create an inter-racial relationship.

Then came Vice Admiral Amilyn Holdo—a high-ranking officer seemingly designed to replace Leia. Her role reinforced the idea that military leadership in this new Star Wars was a female-only domain (while the men were relegated to dying on the front lines). Leia herself was almost killed off, but a Disney mandate requiring only one legacy character death per film saved her—for the moment. That death, instead, went to Luke Skywalker, who by that point had been stripped of everything that once made him Luke.

Also sacrificed was Supreme Leader Snoke—the mysterious figure J.J. Abrams had set up to serve as a long-term antagonist and foil to Kylo Ren. Johnson killed him off with little fanfare, dismantling yet another thread of the trilogy’s larger narrative.

To say The Last Jedi was a failure is, ironically, a bit of a misconception. In the eyes of the media and the new wave of fans, it was a masterpiece—an act of bold reinvention that modernised Star Wars through political correctness, progressive ideology, and diverse casting. It became a blueprint for how to take over a beloved franchise and remodel it for a “new era.”

But to many longtime fans—including myself—The Last Jedi was the confirmation of Star Wars‘ decline. By this point, nearly every beloved legacy character was either dead or on the chopping block, while the new characters felt invincible and devoid of meaningful development. Plot armour and deus ex machina moments replaced real challenges and earned growth.

This is where the divide between old and new fans hit critical mass—fuelled by a mainstream media narrative that declared if you didn’t like The Last Jedi, you were toxic, regressive, and no longer a “true fan.”

But behind the scenes, some changes were already in motion for the final instalment of the Star Wars series—now officially titled The Skywalker Saga. In between the main episodes, Disney began releasing standalone films set in different parts of the timeline, either before Episode I or exploring other corners of the galaxy.

The first of these was Rogue One—the story of the pilot and team that secured the Death Star plans for the Rebellion, setting the stage for Episode IV: A New Hope. This was also a Kennedy production, again centred around a strong female lead.

But unlike The Force Awakens or The Last Jedi, Rogue One didn’t centre around a flawless, fan-fiction-tier protagonist who could do everything without struggle. Instead, it offered a well-written story filled with unique, flawed, and interesting characters. It felt like a proper Star Wars tale—familiar yet fresh. For once, both sides of the fan divide found common ground, with Rogue One earning praise for adding depth and nuance to the universe.

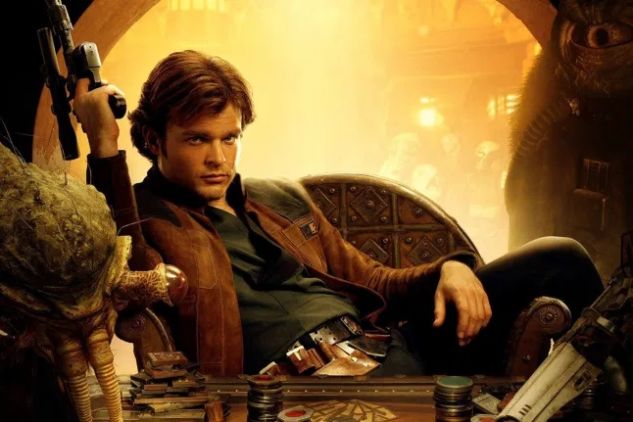

The second standalone film, however, didn’t fare nearly as well. Solo: A Star Wars Story was intended to explore the origin of one of the franchise’s most beloved characters: Han Solo. But rather than honour what made Han iconic, the film stripped away much of what fans knew and loved—recasting him not as a charismatic rogue but as a brash, egotistical, borderline misogynistic playboy.

From the start, Solo was plagued with problems. Parts of the script were leaked online early, giving fans an unwanted preview of some of the film’s weaker elements. Unlike future cases where leaks led to late-stage rewrites, Disney charged ahead with the production as planned.

When Solo finally released, the media quickly labelled it “a throwback to the dated Star Wars of old,” and placed the blame for its underperformance squarely on the same fans who had criticised The Last Jedi. Once again, the message was clear: if you weren’t onboard with Disney’s new vision for Star Wars, you were the problem.

And with that, the fan divide deepened even further.

The trouble surrounding Solo, combined with a growing chorus of discontent from longtime fans, eventually forced Disney to take action—sometimes bypassing Kathleen Kennedy entirely when needed. As a result, Disney cancelled all planned Star Wars side-story films, including the highly anticipated Boba Fett project, and brought back J.J. Abrams to direct the final instalment of the main saga, hoping he could salvage the mess left behind by The Last Jedi.

Many of these decisions were driven by just how hard Solo tanked at the box office. The film barely made back its production budget, let alone generated a profit. This alarmed Disney, especially with the upcoming launch of their latest theme park attraction: Galaxy’s Edge. The new area, located within Disney Parks, was based entirely on the Disney-era Star Wars films and side stories—a massive investment that now looked shaky given the fan backlash and declining interest.

Adding fuel to the fire was the growing number of public outcries from people directly involved in the productions of The Last Jedi and Solo—none louder than Luke Skywalker himself, Mark Hamill.

At first, Hamill seemed happy to return to the role that made him famous, posting cheerful tweets around his brief appearance at the end of The Force Awakens. But his tone shifted dramatically after The Last Jedi. Hamill began expressing disappointment and disillusionment—not only with how his character was handled but with the direction of the franchise as a whole.

He publicly stated that the version of Luke in the Disney trilogy felt like a completely different person. He jokingly referred to the character as “John Skywalker”—someone who looked like Luke but didn’t act like him at all. Hamill frequently commented that it felt as though no one involved with the new films had even seen the originals, let alone understood or respected the legacy of the characters. He expressed frustration that his Luke was distant, jaded, and fundamentally unlike the hopeful, idealistic Jedi created by George Lucas.

Hamill’s criticisms weren’t confined to cryptic tweets either. He voiced his concerns in numerous interviews—both online and in traditional media—making it clear that he didn’t support Kennedy’s vision for Star Wars. And when one of the most beloved stars of your franchise begins publicly criticising the direction it’s going, you have to start paying attention.

Disney noticed. And it was clear: something had to change.

But Disney had one last kick to the franchise’s nuts to deliver.

The Rise of Skywalker landed with the force of a 1990s Mike Tyson punch to the collective gut of fans. After The Last Jedi had burned everything to the ground, J.J. Abrams was left with the impossible task of fixing the damage, addressing fan backlash, and somehow wrapping up the saga in a way that would satisfy everyone. It was a no-win situation—but to his credit, Abrams tried. Yet one last obstacle remained: Kathleen Kennedy.

Kennedy was determined to preserve the changes she and Rian Johnson had implemented in The Last Jedi. She pushed to keep Rose Tico in a lead role, maintain Admiral Holdo as the head of the Resistance, and effectively sideline Leia (though Carrie Fisher’s untimely death forced some changes). She also wanted Rey to remain “a nobody”—yet still somehow become the new Chosen One—solidifying her “The Force is Female: Forever” vision.

Abrams, however, walked a tightrope. He kept a few of Kennedy’s inclusions, but leaned more heavily into what fans actually enjoyed about The Force Awakens: mystery, nostalgia, and that sense of something new. The result? The Rise of Skywalker became a disjointed mash-up of past and present—a frantic attempt to please everyone, and in doing so, satisfying no one. The story was messy, the pacing rushed, and the ending widely panned.

By the time the film was releasing, I already had a good idea of what was coming. A user on Reddit had leaked the production script and exposed which scenes were added or changed due to reshoots after the leaks hit. I tried to avoid spoilers—I wanted to test whether my own predictions for the film would be accurate. But just two days before seeing it, I caved and read the leak.

Turns out, I was mostly right.

What I didn’t predict was the return of Emperor Palpatine—a last-minute stand-in for Snoke, who had been unceremoniously killed off in The Last Jedi. Kylo Ren got his redemption arc, only to die in Rey’s arms. Rey discovered her true lineage—but hated it so much that she randomly chose to call herself “Skywalker” for no logical reason at all.

Leaving the cinema on opening day—with maybe 20 other people in a 150-seat theatre—I knew deep down: Star Wars, as I had known and loved it, was dead.

With The Rise of Skywalker bringing the Star Wars saga to a close, that special feeling I once had for the series is gone. What was once a source of joy, nostalgia, and connection has been overshadowed by a mess of political corporate nonsense—thanks to Kathleen Kennedy, Rian Johnson, and a Disney board too blind or too stubborn to see what they were destroying. The bond I had with Star Wars, forged through cherished memories—watching the first six films in the cinema with my little brother, hearing my mom share her stories of seeing the originals on the big screen—feels tainted now.

When I look at the old VHS tapes, the DVDs, or even the Blu-rays on my shelf, I hesitate. The first thing that floods back isn’t the magic of the original trilogy or the excitement of the prequels—it’s the bitter taste left by the Disney trilogy and the deep divide it caused in a fanbase that once felt united.

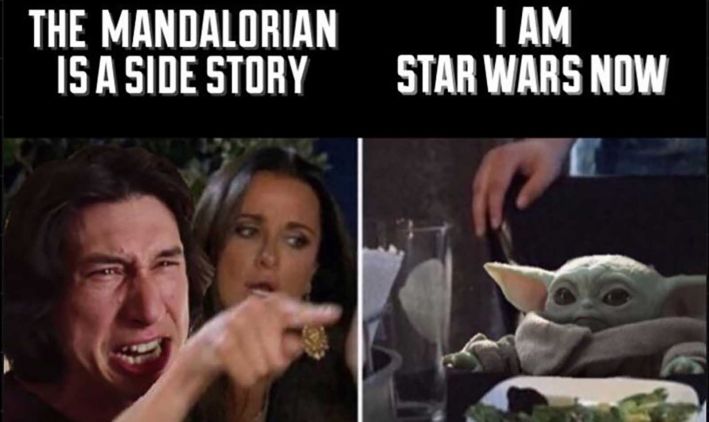

Still, there may be a glimmer of hope. The non-movie projects like The Clone Wars, Rebels, and The Mandalorian have proven that good Star Wars stories can still be told—stories that seem to honour the past while offering something new, free from the baggage and corporate meddling that now stains the films forever.